Research

Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS)

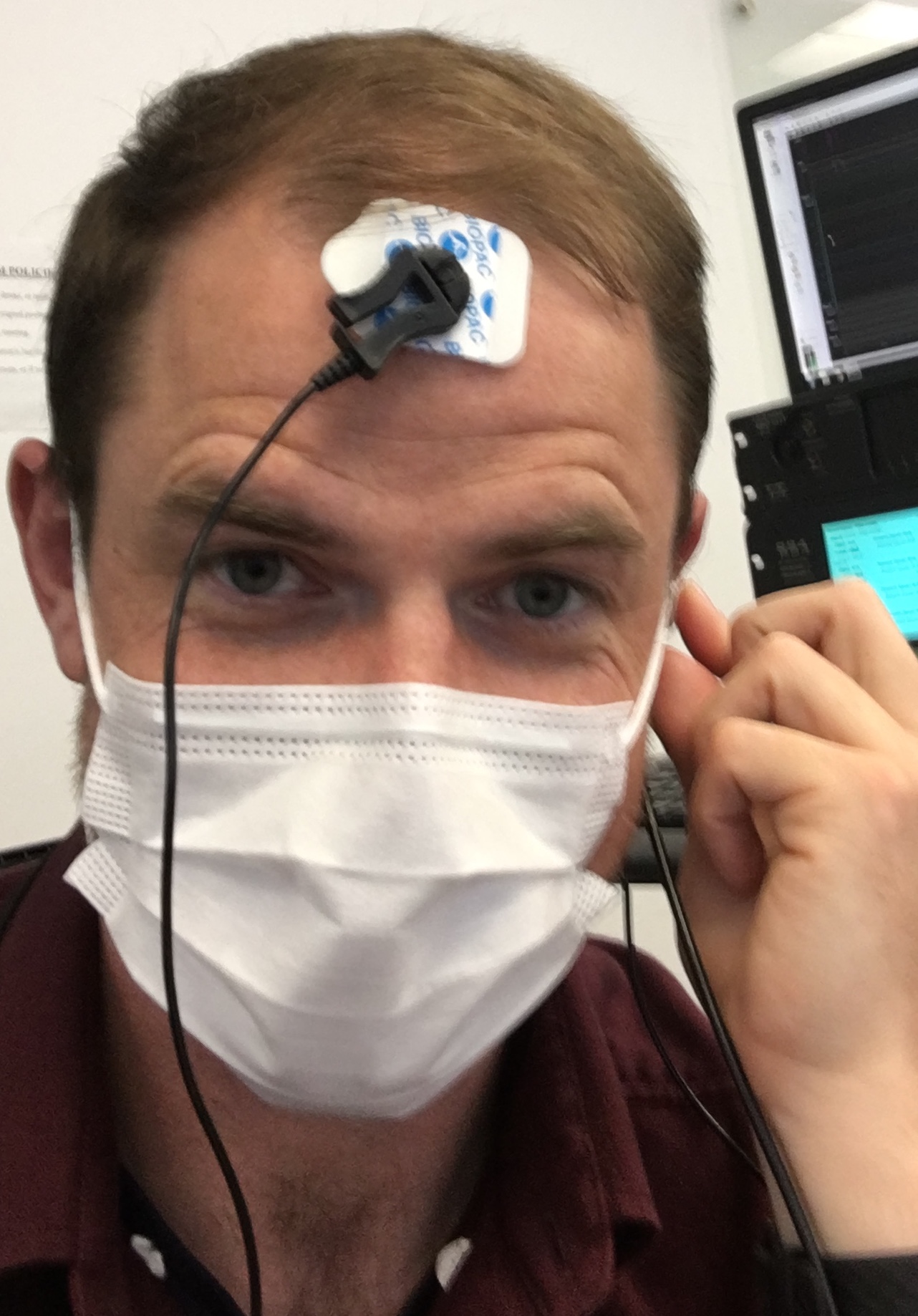

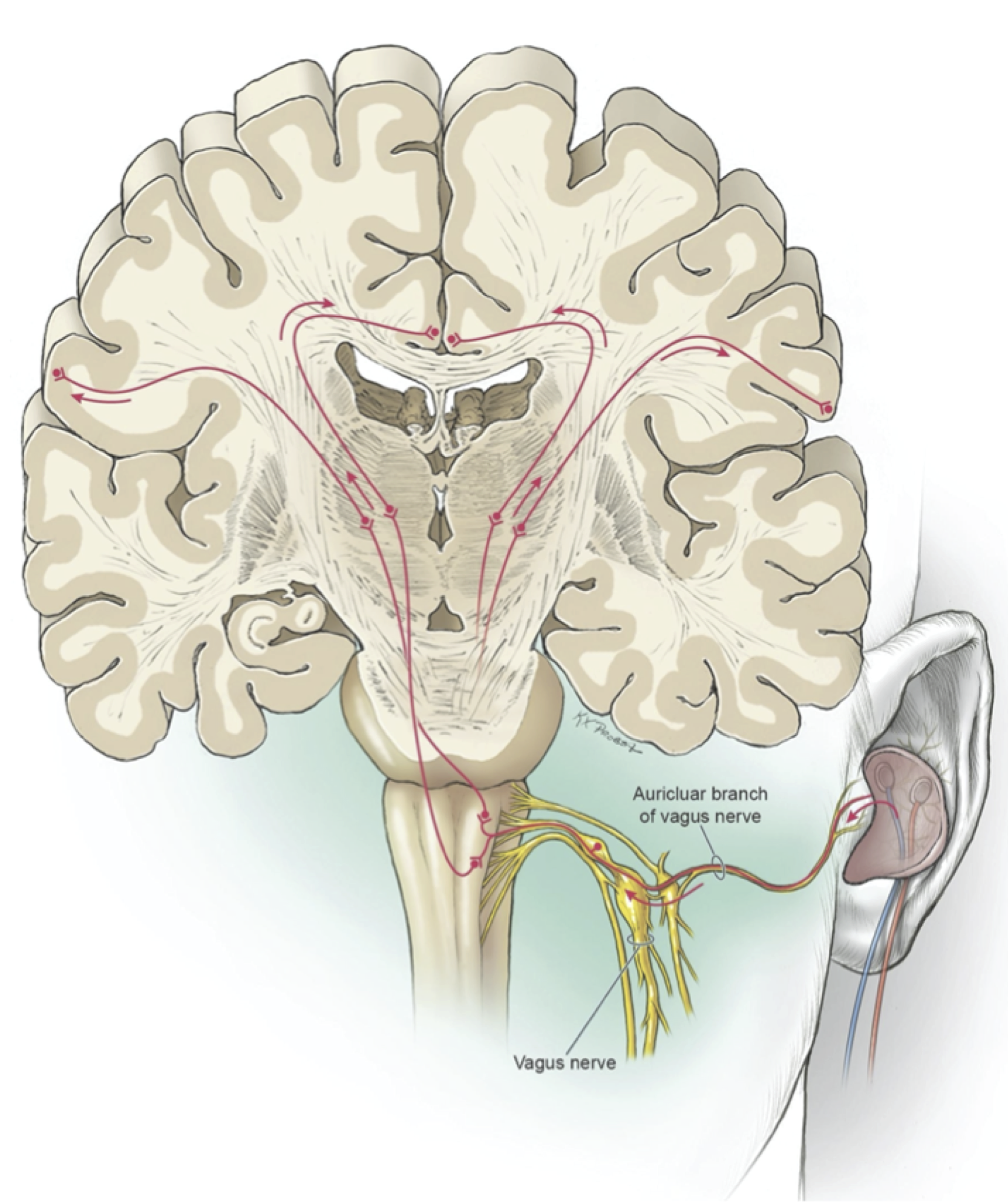

Working with Dr. Matthew K. Leonard at UCSF and collaborators at the University of Iowa and the University of Pittsburgh, I have been conducting behavioral and physiological research on the effects of a neuromodulatory technique called vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Initially approved as a treatment for epilepsy in 1997, VNS involves the implantation of a cuff electrode around the cervical branch of the vagus nerve, located in the neck, and a signal generator/battery in the chest (iVNS). More recently, a non-surgical alternative has been developed that targets the auricular branch of the vagus nerve using transcutaneous surface electrodes (taVNS).

While the application space of both iVNS and taVNS is currently undergoing rapid expansion, fundamental questions have yet to be answered about its mechanisms and efficacy, particularly with regard to tailoring stimulation and treatment protocols to specific individuals and applications, such as second language acquisition or motor rehabilitation. For example, though research in non-human animal models has demonstrated that moderate amplitude VNS can rapidly drive neural plasticity, similar paradigms applied to human participants do not produce uniform increases in learning (Llanos et al., 2020).

In addition to behavioral studies demonstrating that taVNS can increase performance in behavioral tasks, this research also included detailed neurophysiological research. Working in collaboration with individuals who had VNS implants, for whom VNS had been ineffective for unknown reasons, and were undergoing invasive intracranial electrophysiological monitoring as part of their clinical care, we found that taVNS can produce similar changes in neural activity as iVNS (Schuerman et al., in revision).

While we were able to demonstrate that taVNS can effectively modulate neural activity and behavior, we still do not understand exactly what drives variability in responses. Understanding this variability will be crucial for translating our research into real-word applications, such as neuroscience-based interventions for enhancing language learning or speech and language rehabilitation therapies.

Sensorimotor experience in speech perception

Sensory feedback is extremely important for speech production. Delay auditory feedback by a tenth of a second or so and the task of producing fluent speech becomes extremely difficult. The experience of generating a motoric action and then perceiving the sensory results of that action (for example, bringing your hands together and hearing the resulting clap) constitutes sensorimotor experience.

In speech production, this sensorimotor experience is crucial for building our knowledge of the law-like relationships between the movements of our articulators (tongue, jaw, vocal folds) and the sounds that are produced. However, what is more controversial is whether this knowledge and experience has any effect on the way that we perceive speech.

In my doctoral research, I examined the relationship between speech perception and production by investigating the role of sensorimotor experience in speech perception, using word recognition and speech perception experiments such as the one detailed in the following video:

These experiments demonstrated that sensorimotor experience can update mappings between acoustics and linguistic categories and modulate word recognition under specific conditions. However, the effects were relatively subtle, suggesting that sensorimotor experience plays a more modulatory rather than crucial role in speech perception.